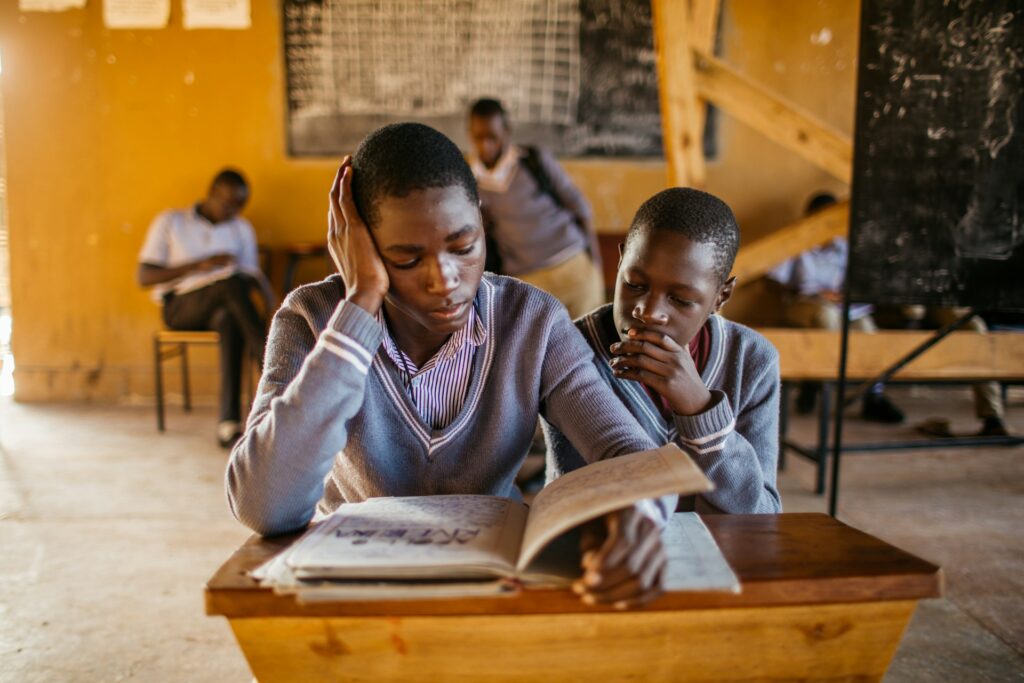

The Importance of Copyright Exceptions for Teachers and Learners

by Dr. Mugwena Maluleke, President of Education International (EI) and General Secretary of the South African Democratic Teachers’ Union (SADTU) On 21 May 2025, the Constitutional Court in South Africa will consider the constitutionality of the Copyright Amendment Bill passed by parliament in 2019 and again in 2024. The new Bill introduces exceptions and limitations to copyright to allow educators to copy, share and adapt excerpts of copyrighted learning materials in the classroom. In this contribution to the debate, Mugwena Maluleke highlights the education crisis facing millions of learners, especially in Africa and the Global South, and the importance of copyright reforms that increase access to learning materials. This article was first presented as a keynote input to the Conference on “Copyright and the Public Interest in Africa and the Global South on 6th Feb 2025 in Cape Town. You can watch the video recording of this presentation here. Dear colleagues, It is an honour to join you today in Cape Town as we reaffirm our shared mission of ensuring equitable access to knowledge and protection of traditional knowledge for Africa. Without reiterating much of what Dr. Schönwetter has eloquently stated in his welcoming address, I extend my gratitude to all those involved in hosting this conference and to all of you attending. Thank you for your commitment to copyright law reform. Reflecting on my childhood in rural Limpopo, we were compelled to learn in English and later in Afrikaans, which led us to stand against the apartheid government in 1976. We were never given the opportunity to learn in our own language. This experience underscores the profound impact that learning materials have on a child’s potential in school. In the quest for knowledge equity, every child deserves the right to learn in their own language. Today, I stand before you not only as the President of Education International but also as the General Secretary of the South African Democratic Teachers Union, representing more than 70% of educators and education workers in South Africa. Charles Darwin, the father of evolution, once said, “It is not the most intellectual of the species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives; but the species that survives is the one that is able best to adapt and adjust to the changing environment in which it finds itself.” The Global Status of Teachers Report, launched on the International Day of Education, January 24 this year, revealed a shocking shortage of 44 million teachers worldwide. A major catalyst for this shortage is the inability to attract and retain teachers due to inadequate conditions for providing quality teaching. Debrah Ruh, a global inclusivity strategist, noted that “accessibility allows us to tap into everyone’s potential.” UNESCO’s Framework for Action recognizes knowledge as part of the right to education for a reason: it is crucial for teachers to have access to teaching and learning materials specifically designed for educational purposes. Fair copyright legislation is essential to enable teachers to adapt and use materials, enrich them, make them context-specific, decolonize our knowledge production and consumption in education, and address an increasingly diverse student body. DECOLONISATION OF KNOWLEDGE and DECRIMINALISATION OF TEACHERS Having mentioned decolonisation of knowledge production and consumption in education, I must add that this implores us to embark on a journey of decolonisation, peeling back the layers of oppression that have been ingrained in our consciousness. This is not merely an act of dismantling the physical symbols of colonialism, but a profound transformation of our mental landscapes. As we lift the veils of ignorance and prejudice, we must replace them with the light of wisdom and understanding. Decolonisation is a reawakening, a reclamation of our heritage and identity. May I also add that education is the bridge that connects our past struggles to our future triumphs. The right to education is a fundamental human right. Our teachers should not be criminalised for striving to provide quality education to our children. Unfortunately, copyright laws for education are often overly restrictive, creating barriers for teachers and the right to education. Global EI research shows that teachers in many Latin American and African countries are particularly disadvantaged by copyright legislation, forcing them to work in legal grey zones or stop using important teaching materials. The use of digital materials and adaptations for children with disabilities poses a particular challenge for the teaching profession. Among 37 countries studied in a recent report by wireless connectivity specialist Airgain, South Africa ranks as one of the worst countries for digital readiness. THE GLOBAL EDUCATION CRISIS Recent studies highlight the urgent need for improved access to education. The 2025 Global Estimates Update by Education Cannot Wait reveals that 234 million school-aged children in crises worldwide require urgent support to access quality education, an increase of 35 million over the past three years. Refugees, internally displaced children, girls, and children with disabilities are among the most affected. The report emphasizes that these growing needs are rapidly outpacing education aid funding and calls for urgent additional financing to address this global silent emergency. Access to appropriate learning materials is a key strategy for achieving the first means of implementation (4a) under SDG4. The supporting Framework for Action Education 2030 highlights access to learning materials as one of the core strategic approaches for implementing the goal: “Education institutions and programs should be adequately and equitably resourced, with safe, environment-friendly, and easily accessible facilities; sufficient numbers of quality teachers and educators using learner-centered, active, and collaborative pedagogical approaches; and books, other learning materials, open educational resources, and technology that are non-discriminatory, learning conducive, learner-friendly, context-specific, cost-effective, and available to all learners – children, youth, and adults.” At the heart of Education International’s Go Public, Fund Education campaign is the principle of putting people before profit. The message is clear: we want creators and authors of material to be compensated fairly, but we do not want intermediaries in the copyright business, such as publishers and streaming executives, to create profit margins that deter access to learning materials