Public AI Launch, and Some Thoughts on Copyright

I attended the exciting launch of a series of papers and reflections on “Public AI” at the EU Parliament this week. The core of the idea is that the non-US/China

I attended the exciting launch of a series of papers and reflections on “Public AI” at the EU Parliament this week. The core of the idea is that the non-US/China

It’s time to put people back into the Intellectual Property system. Currently IP tends to reproduce inequality. IP should support public goods such as health and education. We need to

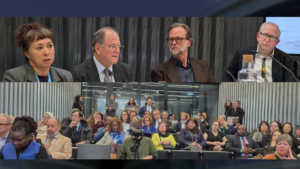

At a packed event at the Geneva Graduate Institute on 3rd December 2025, the Centre on Knowledge Governance held its official launch. The launch featured top thinkers and high level

This week our research team published a series of new reports. These relate to the work streams in the upcoming Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights (SCCR) at the

The timeline presented below details the progression of discussions within the WIPO Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights (SCCR) regarding Limitations and Exceptions (L&Es) to copyright. This detailed chronology, spanning from 1996 to

Sean Flynn, Director of the Centre on Knowledge Governance was featured in GLOBE #36, the review of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

The World Intellectual property Organization (WIPO) has published four new proposals on ways forward for some of its key work streams in the Standing Committee on Copyright and related Rights

Today the Geneva Centre on Knowledge Governance presents a series of Case Studies on AI for Good in Africa and the Global South. These grew out of our work on Text

The rapid development of generative AI has sparked intense debate over how, or even if, creators should be compensated when their copyrighted works are used to train commercial AI systems.

On 25 September, former Director of the Traditional Knowledge Division at the World Intellectual Property Organization Wend Wendland will deliver a lecture on the landmark World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

Luca has a PhD from the UFRJ Graduation Program on Public Policy, Development and Strategies (PPED/UFRJ) with a thesis on ‘Copyright and AI Generated Works’ and is a Director of the Brazilian Copyright Institute. He is a research fellow at the Centre for IT & IP Law (KU Leuven) and a post-doctoral researcher at the National Institute of Citizen Science in Brazil. He is a guest professor at the Graduation Program on Public Policy, Development and Strategies (PPED/UFRJ) and professor at the Specialization Program on Intellectual Property Law at PUC-RJ.

Dr. Susan Isiko Štrba combines teaching and research with providing policy and legislative advice and technical training to governments, intergovernmental organizations and civil society. She focuses mainly on human rights, intellectual property (IP), trade and development. Dr Isiko Štrba is the author of International Copyright Law and Access to Education in Developing Countries: Exploring Multilateral Legal and Quasi-Legal Solutions, a leading guide to the functioning of international copyright law for the public interest in developing countries. She has also published numerous journal articles in the field of human rights, trade, IP and development.

She currently researches the interface of technology, intellectual property and the African Continental Free Trade Area. She is a member of the International Association for the Advancement of Teaching and Research in Intellectual Property (ATRIP) and a member of the Executive Council of the Society of International Economic Law (SIEL). Dr Isiko Štrba has taught Intellectual property, competition law and human rights in various institutions including: the Boston University (Geneva International Campus), The Graduate Institute, Trade Policy Training Centre in Africa (TRAPCA), the International University in Geneva, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa and the WIPO Academy.

Andrés Izquierdo is Senior Research Analyst for our project on the Right to Research in International Copyright. He conducts high-impact research, provides training to a global network of change-makers, and connects a global academic network to the work of global and domestic organizations that represent researchers, libraries, museums, archives, educational and research institutions.

Before joining PIJIP, Andrés Izquierdo practiced law through his award-winning intellectual property and cyber law practice in Colombia. He has been named one of the best entertainment law attorneys in Colombia by the publications Best Lawyers (2020), and top Intellectual Property practitioner by Chambers and Partners (2014-2020), and is author of the book Cyberlaw by Wolters Kluwer. Izquierdo was previously Business and Legal Director for Sony Music Entertainment in the Andean Region, and litigation partner in Palacio, Izquierdo & Ballesteros, an intellectual property law firm in Colombia. He has LLM degrees in Intellectual Property from American University Washington College of Law and from the University of Turin – WIPO, and a law degree from Universidad de Los Andes.

Ben Cashdan is a economist and television producer in South Africa. He was an economic advisor in the South African Presidency under President Nelson Mandela, focusing on capacity building and local economic development. Since 2000 Ben has served as executive producer of a number of television series on democracy and development for global broadcasters. In 2015 Ben co-founded ReCreate South Africa, a coalition of creators and users of copyrighted material in South Africa, working together for fair and balanced copyright reform and access to knowledge.

Ben has a masters degree in Social and Political Sciences from Kings College Cambridge and a Postgraduate Certificate in Economics from the London School of Economics. Ben also continued his postgraduate studies at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland in the Department of Economic Geography. He was South African producer for Harry Belafonte’s biographical documentary Sing Your Song. Ben has also produced 4 episodes of The World Debate on BBC World News. He developed and produced the first season of South2North on Al Jazeera English, the first global talk show to be produced in Africa for a major global broadcaster. In December 2013 Cashdan produced an episode of BBC Question Time on South Africa after Mandela.

Ben has directed a number of broadcast media projects on democracy and development in partnership with agencies including the World Economic Forum, the United Nations Development Programme and the African Leadership Academy.

Professor Flynn researches and teaches on the intersection of intellectual property, international law, and human rights. Professor Flynn designs and manages a wide variety of research and advocacy projects that promote the public interest in intellectual property and information law. Professor Flynn Chairs the Global Expert Network on Copyright User Rights and is a founding member of the Global Congress on Intellectual Property and the Public Interest.

He is Editor in Chief of Infojustice.org, a leading public interest law and policy blog. He is a special faculty appointment at American University Washington College of Law, visiting Scholar at the University of Amsterdam’s Institute for Information Law (IViR), and Senior Research Associate at the University of Cape Town’s Intellectual Property Unit. Prior to joining WCL, Professor Flynn completed a Fulbright Fellowship, was clerk to Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson, South African Constitutional Court and Judge Raymond Fisher, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, practiced law at Spiegel & McDiarmid and the Consumer Project on Technology, and served on the policy team advising then Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Deval Patrick.